CPR and Defibrillation in Remote Environments

19th October 2014, revised 7th July 2019 and 4th December 2024

Early, good quality CPR and timely defibrillation are the single most important factor in terms of a successful resuscitation and the positioning of Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) in public areas for use by lay people, with or without formal training, is of clear benefit to the casualty. Most data that exists on the use of Defibrillators in a pre-hospital setting is taken from urban studies where transport to definitive care is relatively fast. In one study (1) AEDs have increased survival from Cardiac Arrest to nearly 74%, survival to hospital discharge. But is the same true when we are far from help?

If the casualty is unconscious and not breathing, they are already dead.

Clinically, this statement is not strictly true as there may be other signs of life which the lay rescuer may not be able to determine but this seemingly callous assumption is made for several reasons, not just for the casualty’s benefit, but for everyone’s:

There are several reasons why the casualty may not be breathing, the worst case scenario is that they are in Cardiac Arrest - an inability of the heart to circulate blood either due to an absence of electrical activity or chaotic, uncoordinated electrical activity. If this is the case they will need resuscitation to return normal circulation. This is time critical.

If the casualty is not breathing for any other reason, without oxygen they are likely to go into Cardiac Arrest with in 10 minutes. (2) Time spent deciding if they are dead or not or the reason behind why they are not breathing is wasted time.

In short, they are either in cardiac arrest, or they soon will be. Regardless of cause, the treatment is the same.

There are exceptions to this including hypothermia, lightening / electrocution, drowning and children. The latter will be discussed in separate articles.The best possible outcome is the casualty is successfully resuscitated and makes a full recovery but the absolute worst outcome is that they stay dead. It cannot get any worse.

If we work on the assumption that they casualty is already dead, your expectation will usually be met.

Because of the misconception that CPR will ‘bring them back to life’ it is a typical for a First Aider to place blame on themselves when a casualty is not successfully resuscitated: “Maybe I did something wrong?” or “Maybe I should have done it better?”

By changing our perspective, any failure to successfully resuscitate can never be seen as anyone’s fault. They didn't die as a result of the treatment you provided, they just stayed dead.

So why do we do CPR?

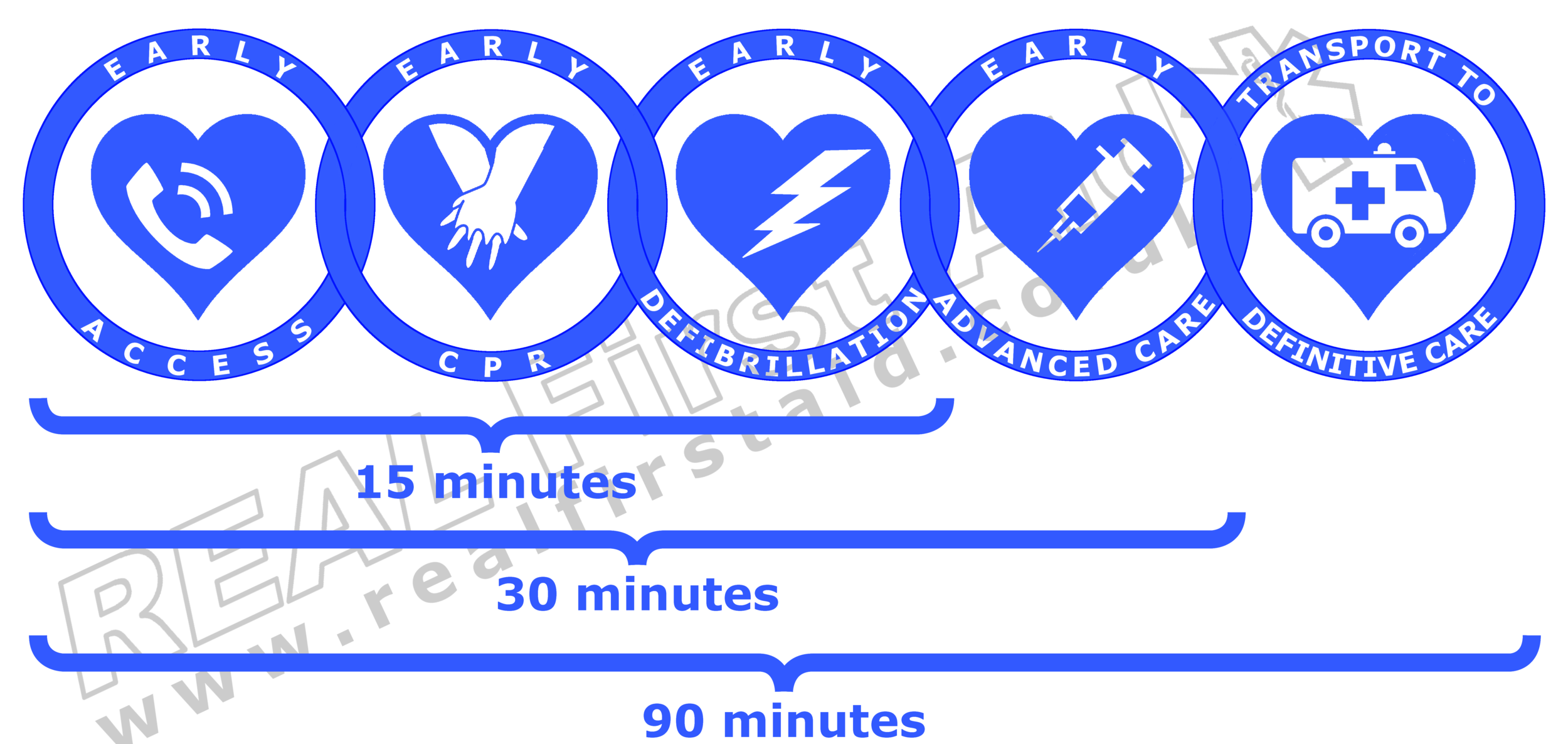

CPR on its own is highly unlikely to successfully resuscitate a casualty in Cardiac Arrest but it may introduce and circulate a small amount of oxygen to delay cardiac and cerebral ischemia. CPR also has a specific role in a combination with a sequence of other interventions known as the Chain of Survival.

In 1988 Mary Newman coined the phrase “The Chain of Survival” at a national conference on Citizen CPR (3) which formed the basis for her 1989 article “The Chain of Survival Takes Hold” (4).

This model demonstrates the sequential protocol for treating any casualty who is assumed to be in Cardiac Arrest for the very simple aim of increasing their chance of recovery. Like any chain, it is only as strong as is weakest link; in terms of successful resuscitation the weakness in each link is time delay.

Early access:

As soon as it is recognised that the unconscious casualty is not breathing - or indeed not breathing normally - contact the emergency services and summon a defibrillator. While Basic Life Support is concerned with resuscitation of a casualty in Cardiac Arrest the protocol is triggered by the absences of normal breathing. Checking for the absence of a carotid pulse is not only an unreliable indicator of cardiac arrest for the lay rescuer (5) (especially if the casualty is hypothermic or hypovolaemic) it is also time consuming - a delay of 2 minutes in the initial call for help reduces survival rates by 50%.(1)

Regardless of cause, if the casualty is not breathing they are either in cardiac arrest or they will be soon! Immediately summon a defibrillator or call for help.

Early CPR

Effective CPR will circulate approximately 25-33% blood volume (6, 7) – not enough to sustain life but enough to delay tissue cell death. Again, the chance of survival decreases by 50% after only 3 minutes delay of CPR. (1)

60% of Cardiac Arrests are caused by Heart Attack (Myocardial Infarction) with 50-80% of these casualties being in Ventricular Fibrillation (8, 9). This is a shockable rhythm which may be reverted by defibrillation. CPR alone will never revert the heart’s electrical activity to a normal rhythm but effective CPR may keep the heart in this shockable state for a minutes longer (10).

Once help has been called or a defibrillator summoned, start CPR.

Early Defibrillation

Defibrillation is the only method that exists to depolarize the abnormal electrical activity in the heart and yes, this is time critical too. From the moment the heart goes into arrest, every cell in the body is being deprived of oxygen, including heart tissue. Prolonged cardiac hypoxia causes irreversible damage which if left untreated will cause the heart to stop completely. Once there is an absence of electrical activity, defibrillation with an AED will not work. Even without CPR, survival rates with defibrilation within 3 minutes of arrest are as high as 60% (5)

As soon as it is practical, stop CPR, turn on the defibrillator and follow the instructions.

If a second rescuer is available they prepare the defibrillator without interrupting your CPR.

Early Advanced Care

While timely CPR and Defibrillation will increase the casualty’s chance of recovery they by no means guarantee it. Whether normal circulation has resumed or not, the casualty will need Advanced Life Support; advanced interventions, drugs and techniques. A defibrillator may be able to return normal electrical activity to the heart and, as a result, normal circulation but it does not deal with the root cause of the arrest which may still be present. One estimate of the maximum time limit for Advanced Care is 30 minutes and 90 minutes for transport to definitive care. (11)

Resuscitation in Remote Environments

In a remote environment we may be able to summon help and commence CPR quickly but without the remaining links of the chain in place, within their respective time limits, the chance of recovery is negligible.

It is sometimes worth attempting resuscitation, if you are willing and able, even if you suspect it may be futile:

Your conscience is clear, safe in the knowledge that you followed protocols and did everything you reasonably could, without any “what if’s?”

Witnessing an attempt to resuscitate the casualty is an important factor in enabling other people, especially family if they are present, to work through the grieving process.

Should you carry a Defibrillator in a remote environment?

Two important factors to consider are:

Defibrillation is simply one link of the chain: Even if the casualty is successfully resuscitated by the lay rescuer, they will still require pre-hospital Advanced Care as well as transport to definitive care in hospital which cannot be guaranteed in a remote environment.

The heart may remain in Ventricular Fibrillation for 10-12 minutes from collapse , a few minutes more if preceded by effective CPR (12, 13). With an AED close to hand we may be able to defibrillate well within this timeframe, however, successful recovery is still dependent on Advanced Life Support within 30 minutes and transfer to definitive care within 90 minutes.

If the casualty is able to be defibrillated quickly but the remaining care is delayed is there any point in defibrillating or are we merely delaying the inevitable?While timely defibrillation can increase the chance of survival for some casualties, a defibrillator cannot not guarantee successful resuscitation– a defibrillator cannot shock all heart rhythms and not all causes of Cardiac Arrest can be resolved by defibrillation.

One common misperception of a clinical scenario in a remote location requiring an AED is that lightning injury is likely to induce ventricular fibrillation; the strike must occur at the exact time of the peak of the T wave to precipitate this shockable dysrhythmia; instead, asystole is much more likely to occur (14). The likelihood of asystole is also greater than ventricular fibrillation in drowning (15).

As with any First Aid Needs Assessment, whether a Defibrillator should be carried as part of your kit will depend on several factors including, but not limited to:

Proximity to definitive care

If you are unable to access Advanced Care within 30 minutes and Definitive Care within 90 minutes it is likely that if the casualty is resuscitated, the casualty is likely to arrest again.Client Group

Older casualties, in poor health with pre-existing medical conditions are more likely to experience Cardiac Arrest than young, fit, athletic people in good health.Activity

Strenuous activities, stressful working environments and challenging climates are all factors which will increase the likelihood of Cardiac Arrest in come casualties.

The decision to provide a defibrillator is simply one decision to make following your Risk Assessment and Needs Analysis. If your risk assessment indicates that the probability of having to resuscitate a casualty is realistic, other elements of your Emergency Plan must also be adjusted including:

The level of medical care immediately available

The standard of medical equipment immediately available

Evacuation and medical repatriation plans

If the Emergency Plan cannot cater for this risk, the risk must be brought down to a level that can be catered for. This can be achieved by reconsidering the venue choice, client group and health screening and the type of activity or environment.

When to stop CPR in a Remote Environment

There is no definitive guidance on when to stop CPR in a remote environment. Countries which subscribe to the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (including the US and UK) are advised to stop CPR when:

qualified help arrives and takes over OR

the victim starts to show signs of regaining consciousness, such as coughing, opening his eyes, speaking, or moving purposefully AND starts to breathe normally, OR

you become exhausted.

In addition to this two sources suggest it is reasonable to stop CPR in a remote environment after 30 minutes (16, 17).

Managing Death in Remote Environments

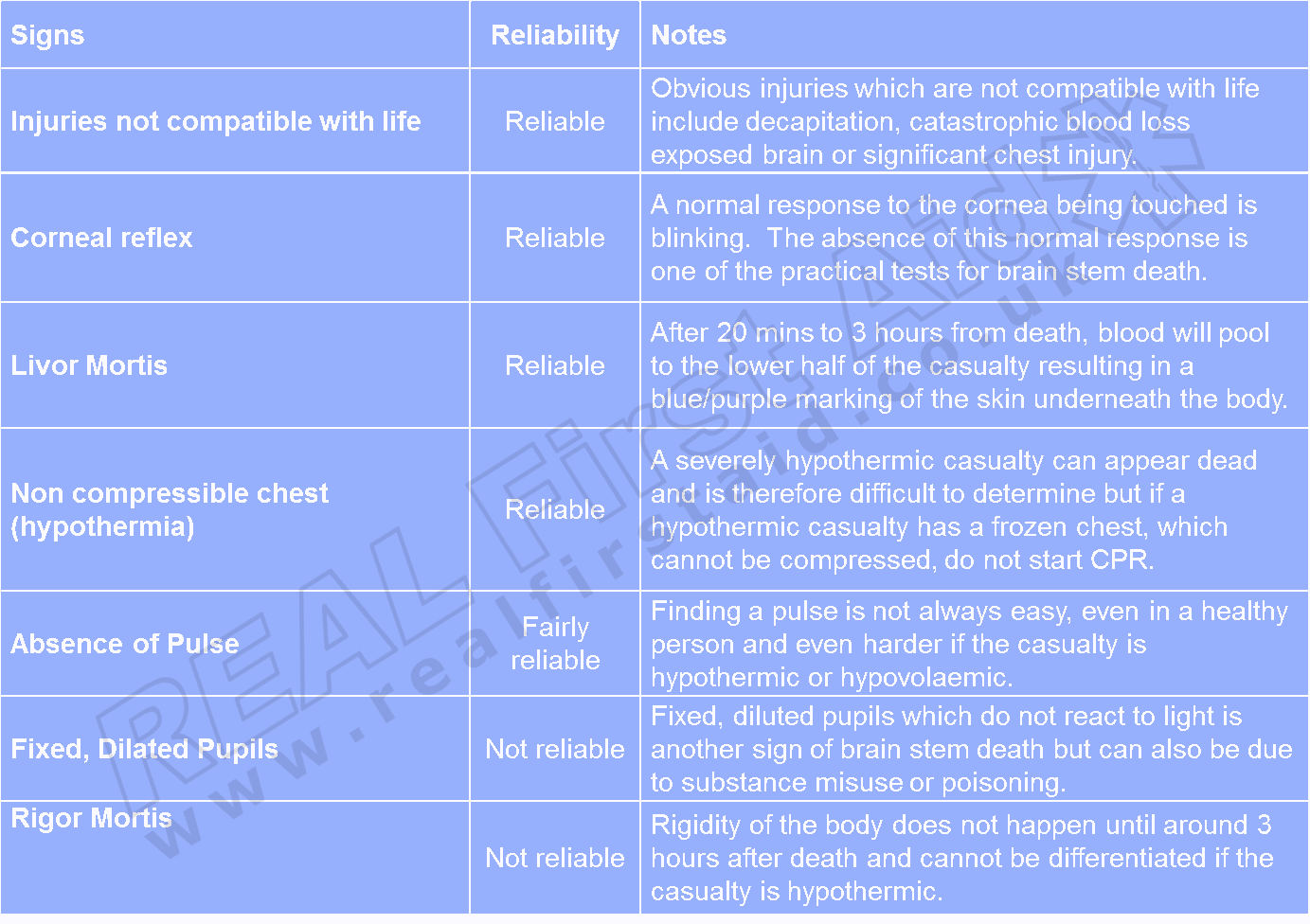

It may not be appropriate to start CPR if the casualty is clearly dead; the experience may be distressing for the rescuer as well as those watching, it may be unethical or it may consume time, resources and effort which could be better applied elsewhere.

Recognition of Life Extinct (ROLE) is the process of recognising when someone is actually dead.

A classic comment you may hear is that “only a doctor or coroner can declare someone dead.” Well, that is not strictly true.

Doctors do not necessarily certify a death, rather certify the medical cause of death.

The death cannot be registered until after the inquest, but the coroner can provide an interim death certificate to prove the person is dead. This can be used to let organisations know of the death and apply for probate or repatriation.

There are some cases where neither a doctor nor coroner are needed to simply recognize when someone is dead.

In Case of Death in a Remote Environment

Locate and secure the person’s passport, identification and insurance details, medication, diary, camera, mobile phone and diary as these may be used as evidence in an inquest.

Inform the police and, if abroad, the Embassy, Consulate or High Commission; yours and theirs if different. Provide them with the contact details of the person’s next of kin.

All deaths need to be registered in the country you are visiting at the time as well as the deceased’s home country. A death certificate will need to be issued before the body or ashes can be repatriated.

If the casualty has died from an infectious disease, alert the authorities as soon as possible and secure the area from humans and wildlife. Remain together and limit travel unless absolutely necessary.

Do not move the body until you have received permission from the local police. In tribal regions where there is no police, seek permission from the Head of the tribe or village.

You should not interfere with the body to preserve evidence, however, sometimes you will need to cover the body or even bury it depending on how long it will take to be retrieved. Reasons for covering or burial include dignity, infection control and protection of the body from flooding, avalanche, wildlife.

Mark and record the location accurately to aid recovery of the body

Talk about it. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder cannot be underrated. No one is immune to grief and loss and no one should be too proud to talk about their feelings. PTSD is beyond the scope of this article but we cannot stress this enough. When you return home, talk about your experiences and feelings, either with family and friends or with professional counsellors.

Related Article: Hypothermia Guidelines

References

Waalewijn RA, de Vos R, Tijssen JG, Koster RW. (2001) “Survival models for out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation from the perspectives of the bystander, the first responder and, the paramedic”. Resuscitation. Nov;51(2):113-22.

Berg RA, Hilwig RW, Kern KB, Babar I, Ewy GA (1999) “Simulated mouth-to-mouth ventilation and chest compressions (bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation) improves outcome in a swine model of prehospital pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest”. Critical Care Medicine. Sep;27(9):1893-9.

Newman MM (1988) “Early access, early CPR and early defibrillation: Cry of the 1988 Conference on Citizen CPR.” Journal of Emergency Medical Services. 13:30-35

Newman M (1989). "The chain of survival concept takes hold". Journal of Emergency Medical Services. 14: 11–13.

Eberle B, Dick WF, Schneider T, Wisser G, Doetsch S, Tzanova I. (1996) “Checking the carotid pulse check: diagnostic accuracy of first responders in patients with and without a pulse.” Resuscitation. Dec;33(2):107-16.

American Heart Association (2005) “2005 Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care - Part 7.1: Adjuncts for Airway Control and Ventilation”. Circulation. 112: IV-51-IV-57

Jiang L, Jhang J (2011) “Mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitation for patients with cardiac arrest.” World Journal of Emergency Medicine, 2(3)

van Alem AP, Vrenken RH, de Vos R, et al. (2003) “Use of automated external defibrillator by first responders in out of hospital cardiac arrest: prospective controlled trial.” British Medical Journal. 327:1312.

Whitfield R, Colquhoun M, Chamberlain D, et al. (2005) The Department of Health National Defibrillator Programme: analysis of downloads from 250 deployments of public access defibrillators. “Resuscitation” 2005;64:269-77.

Bossaert LL (1997). "Fibrillation and defibrillation of the heart". British Journal of Anaesthesia 79 (2): 203–13.

Vukmir R. (2006) “Survival from prehospital cardiac arrest is critically dependent upon response time.” Resuscitation. 69:229-234.

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). (2000) Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 4: Automated External Defibrillator: Key link in the chain of survival. Circulation 2000;108(Suppl 2):I60-I76.

Cummins RO, Ornato JP, Thies WH, Pepe PE. (1991) Improving survival from sudden cardiac arrest: the “chain of survival” concept: a statement for health professionals from the Advanced Cardiac Life Support Subcommittee and the Emergency Cardiac Care Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation 83:1832-47.

Kleiner JP, Wilkin JH. (1978) “Cardiac effects of lightning stroke”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 240:2757–2759.

Donoghue AJ, Nadkarni V, Berg RA, et al. (2005) “CanAm Pediatric Cardiac Arrest Investigators. Out-of-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest: an epidemiologic review and assessment of current knowledge”. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 46:512522.

Duff J, Anderson R. (2017) "First Aid and Wilderness Medicine" Cicerone, Singapore, p.56

Center for Wilderness Safety (2011) "Wilderness Protocol 1: CPR and Cardiac Arrest." https://www.wildsafe.com/resources/protocols/1.html Accessed 19th October 2014