Pelvic Injury

27th July 2018 updated 18th January 2021

Pelvic injuries can be life-threatening, especially in a remote environment where we are far from help. To safely manage a casualty with a pelvic injury requires a particular understanding of the cause, recognition and treatment.

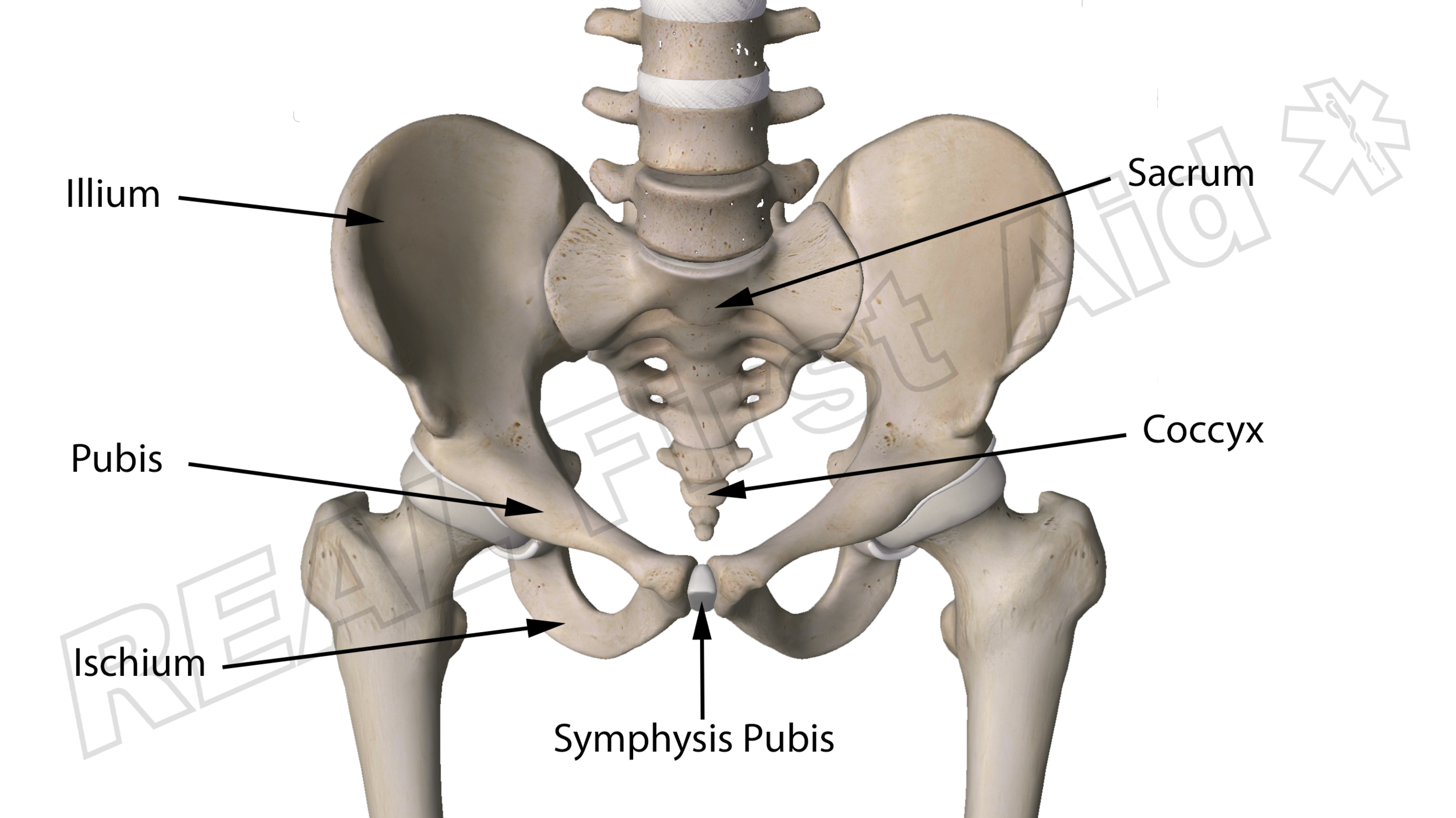

The Pelvis

The pelvis is a large, stable and strong ring-like structure. Each illium is joined to either side of the sacrum - the base of the spine. The 'ring' is completed at the front by a cartilage bridge called the symphysis pubis. This flexible joint is necessary for the pelvis to flex and expand during childbirth. Because all eggs carry the female X chromosome all foetuses start off as females which is why men also have a symphysis pubis. And nipples, but that's irrelevant.

To complicate the situation, a fractured pelvis can become unstable and will require support to stabilise it, especially if the casualty is to be moved. This is essential as the femoral arteries run across the front of the pelvis. Movement of broken bone ends can cause catastrophic internal bleeding.

Contrary to popular belief, The pelvis does not ‘fill’ with blood rather haemorrhage spreads through disrupted tissue planes, extending through the retroperitoneum out of the pelvis into the abdominal retroperitoneum up into the thorax, and anteriorly around the bladder and the anterior abdominal wall. (1) The increase in volume of the pelvis, following fracture, is much less than expected: a large pubic separation of 10 cm corresponds to only a 35% increase in pelvic volume, or 480 cm. (2)

'Closing the pelvis' does not prevent this and as such a pelvic splint is not used to reduce the volume of the pelvis or achieve perfect anatomical alignment. The reduction and stabilisation of the pelvic ring is to reduce the degree of fracture (3), decrease bleeding from the fracture (4-7) while protecting any initial blood clot from disruption. In theory, a small decrease in the pelvic volume (8) may create a tamponade thus reducing venous bleeding. (9-11)

Epidemiology

Casualties who are haemodynamically unstable on arrival to the Emergency Department have a much higher mortality rate than the stable patient(12). Bleeding pelvic fractures associated with hemodynamic instability may have up to 40% mortality (13) whilst Anterior compression injuries ("open book" fractures) are associated with the highest mortality (48%) (14).

Mechanism of Injury

The prevalence of pelvic fracture in patients with blunt trauma is between 5% and 16% (15-18) as the forces needed to break a pelvis are significant. If we think about the type of incidents which can create such forces we think of:

Falls from Height

Anything involving a vehicle - driver, occupant, pedestrian, cyclist etc.

High speed sports impact - skiing, snowboarding or mountain biking etc.

The mechanisms are exactly the same as those for a suspected spinal injury. There is indeed a strong correlation between casualties with spinal cord injury in vehicular incidents and pelvic injury (19).

Anything under tension of compression will break at the weakest points; in the pelvis these likely weak points are:

The joint between the illium and the sacrum - the sacroilliac joint

Where the pelvis is thinnest, such as the rami of the pubis and ischium - the thin bridges at the front of the pelvis.

The symphysis pubis

The acetabulum - the socket the hip sits in

Any damage to these parts can cause instability, threfore we do not move the pelvis. Moving the pelvis can cause further damage, trap nerves or blood vessels or even collapse the pelvic ring. (18). Movement should be limited to the point that no casualty with a pelvic injury should even be log-rolled except for the purposes of airway management (20, 21). A scoop stretcher should be used for all casualty movement.

Assessment

So how do we assess a casualty for a pelvic injury if we cannot move it?

‘Springing the pelvis’ had a poor sensitivity (59%) and specificity (71%) (21). There is also concern that compressing the pelvis can cause further haemorrhage and as a result this technique is no longer recommended. (20, 22)

We are not going to physically assess for a pelvic injury in the field, The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh’s Faculty of Pre Hospital Care Consensus Initial Statement on The Pre-hospital Management of Pelvic Fractures provides an algorithm for pre-hospital decision making (21):

After Scott I, Porter K, Laird C, Bloch M and Greaves I (2013) (21)

A simplified decision tool would be; Are you treating the casualty for a spinal injury? As the incidents which could reasonably cause a pelvic injury are the same as those that could have caused a spinal injury, if you are treating a casualty for a spinal injury, treat them for pelvic injury as well.

Treatment

Current pre-hospital guidance for all suspected pelvic injuries is the early application of a pelvic splint (21).

“If the patient is haemodynamically compromised with a significant mechanism suggestive of a pelvic injury, a pelvic binder should be applied…the pelvic binder is a treatment intervention rather than a packaging device and if the device is thought of as a haemorrhage control device this should promote early application.”

Although definitive evidence demonstrating improved survival with pelvic binder use is lacking, the recommendation for pelvic binder use as initial management of pelvic fracture haemorrhage is overwhelming in both and military practice guidelines. (21, 23-38).

Pelvic Stabilisation

Consideration to pulling the legs out to length (with appropriate analgesia as needed) (21)

Apply a pelvic binder positioned at the Greater trochanter (37-44) – NOT around the waist.

Binding the legs together at the knees and figure of 8 around the ankles and feet should be made. (21)

If applying any traction causes increased pain or further haemodynamic instability then the legs should be strapped together in the position found. (21)

For casualties with lower limb injuries as well as pelvic injuries, there is no evidence that pelvic binders are harmful when applied to patients with proximal femur or acetabular fracture. (27)

The manufacturers of traction splints do not recommend their use with pelvic fractures however, consideration for a device such as the Kendrick Traction Device (KTD) which allows you to work around the problem of hip and groin trauma and may also be applied more rapidly than older devices whilst still allowing reasonable ease of extrication and packaging. (21)

Care must be taken to align the pelvic splint central to the greater trochanters

Long term care considerations

The pressure excreted by the pelvic ling on the boney processes of the greater trochanters, pubis and sacrum can, over time, lead to tissue damage (45-51) as pressure, sufficient to cause pressure sores and skin necrosis, is believed to occur when contact pressures above 9.3 kPa are sustained continuously for more than 2 or 3h (52).

In a comparison of a selection of pelvic binders in 80 healthy volunteers, the pressures exceeded 9.3 kPa at the greater trochanters in all devices whilst used on a spinal board. On a hospital bed this pressure was reduced below the theoretical tissue-damaging threshold. (53)

The polytrauma patient is more likely to be at increased risk of soft-tissue damage due to systemic factors promoting tissue breakdown and trauma associated local soft-tissue injuries. (54-56)

In all cases one should follow the manufacture’s instructions, but consider releasing the binder briefly every 24hrs if being maintained for longer. (27)

Summary

Where a high suspicion of Pelvic Injury exists, a pelvic splint should be applied quickly.

If the lower limbs can be placed into normal alignments the ankles should be stabilised.

The pelvic splint should be centred over the greater trochanters.

Casualty movement should be limited; a scoop stretcher should be used.

Airway management will still take priority

For prolonged care (>24hrs), consider briefly releasing the pelvic splint to prevent tissue damage.

Related Article - An Improvised Pelvic Splint

References

Brohi K. (2008) “The Ideal Pelvic Binder. What's important in a pelvic binder?” http://www.trauma.org/index.php/main/article/657/ Accessed 27th July 2018

Stover MD, Summers HC, Ghanayem AJ, et al. (2006) “Three-dimensional analysis of pelvic volume in an unstable pelvic fracture”. Journal of Trauma. 61:905–908.

Bonner TJ, Eardley WG, Newell N, Masouros S, Matthews JJ, Gibb I, et al. (2011) “Accurate placement of a pelvic binder improves reduction of unstable fractures of the pelvic ring”. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery; British Orthopaedic Association. Nov;93(11):1524-1528.

Cryer HM, Miller FB, Evers BM, Rouben LR, Seligson DL. (1998) “Pelvic fracture classification: correlation with haemorrhage”. Journal of Trauma. 28:973–80.

DeAngelis NA, Wixted JJ, Drew J, Eskander MS, Eskander JP, French BG. (2008) “Use of the trauma pelvic orthotic device (T-POD) for provisional stabilisation of anterior–posterior compression type pelvic fractures: a cadaveric study”. Injury. 39:903–6.

Cole PA. (2003) “What’s new in orthopaedic trauma”. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 85-A:2260–9.

White CE, Hsu JR, Holcomb JB. (2009) “Haemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures”. Injury. 40:1023–1030.

Ward LD, Morandi MM, Pearse M, Randelli P, Landi S. (1997) “The immediate treatment of pelvic ring disruption with the pelvic stabilizer”. Bulletin/Hospital for Joint Diseases. 56:104–6.

Ghaemmaghami V, Sperry J, Gunst M, et al. (2007). “Effects of early use of external pelvic compression on transfusion requirements and mortality in pelvic fractures”. American Journal of Surgery. 194:720–3. [discussion 3].

Grimm MR, Vrahas MS, Thomas KA. (1998) “Pressure–volume characteristics of the intact and disrupted pelvic retroperitoneum”. Journal of Trauma. 44:454–9.

Eastridge BJ, Starr A, Minei JP, O’Keefe GE, Scalea TM. (2002) “The importance of fracture pattern in guiding therapeutic decision-making in patients with hemorrhagic shock and pelvic ring disruptions”. Journal of Trauma. 53:446–50. [discussion 50–1].

Starr AJ, Griffin MA. (2000) “Pelvic ring disruptions: mechanism, fracture pattern, morbidity and mortality: an analysis of 325 patients”. Orthopaedic trauma association meeting.

White CE, Hsu JR, Holcomb JB. (2009) “Haemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures”. Injury. 40:1023–1030.

Mossadegh S, Tai N, Midwinter M, et al. (2012) “Improvised explosive device related pelvi-perineal trauma: anatomic injuries and surgical management”. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 73:S24–S31.

Gustavo Parreira J, Coimbra R, Rasslan S, Oliveira A, Fregoneze M, Mercadante M. (2000) “The role of associated injuries on outcome of blunt trauma patients sustaining pelvic fractures.” Injury. 31:677–82.

Brenneman FD, Katyal D, Boulanger BR, Tile M, Redelmeier DA. (1997) “Long-term outcomes in open pelvic fractures”. Journal of Trauma. 42:773–7.

Grotz MR, Allami MK, Harwood P, Pape HC, Krettek C, Giannoudis PV. (2005) “Open pelvic fractures: epidemiology, current concepts of management and outcome”. Injury 36:1–13

Croce MA, Magnotti LJ, Savage SA, Wood 2nd GW, Fabian TC. (2007) “Emergent pelvic fixation in patients with exsanguinating pelvic fractures”. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 204:935–9. [discussion 40–2].

Nutbeam T, Fenwick R, Smith J. et al. (2021) “A comparison of the demographics, injury patterns and outcome data for patients injured in motor vehicle collisions who are trapped compared to those patients who are not trapped”. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 29;17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-020-00818-6

Lee C, Porter K. (2007) “The prehospital management of pelvic fractures”. Emergency Medicine Journal. Feb;24(2):130-133.

Scott I, Porter K, Laird C, Bloch M and Greaves I (2013) “The Pre-hospital Management of Pelvic Fractures: Initial Consensus Statement”. Emergency Medicine Journal, 30(12) 1070-1072

Grant PT. (1990) “The diagnosis of pelvic fractures by 'springing'. “ Arch Emerg Med Sep;7(3):178-182.

Littlejohn L, Bennett BL, Drew B. (2015) “Application of current hemorrhage control techniques for backcountry care: part 2, hemostatic dressings and other adjuncts”. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. 26:246–254.

Trainham L, Rizzolo D, Diwan A, et al. (2015) “Emergency management of high-energy pelvic trauma”. Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 28:28–33.

Mauffrey C, Cuellar DO 3rd, Pieracci F, et al. (2014) “Strategies for the management of haemorrhage following pelvic fractures and associated trauma-induced coagulopathy”. The Bone and Joint Journal. 96-B:1143–1154.

Langford JR, Burgess AR, Liporace FA, et al. (2013) “Pelvic fractures: part 1. Evaluation, classification, and resuscitation”. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery. 21:448–457.

Chesser TJS, Cross AM, Ward AJ. (2012) “The use of pelvic binders in the emergent management of potential pelvic trauma”. Injury. 43:667–669.

Guthrie HC, Owens RW, Bircher MD. Fractures of the pelvis. (2010) Bone and Joint Surgery; British Orthopaedic Association. 92:1481–1488.

Flint L, Cryer HG. (2010) “Pelvic fracture: the last 50 years”. Journal of Trauma. 69:483–488.

Rommens PM, Hofmann A, Hessmann MH. (2010) “Management of acute hemorrhage in pelvic trauma: an overview”. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 36(2):91–99.

Jeske H, Larndorfer R, Krappinger D, et al. (2010) “Management of hemorrhage in severe pelvic injuries”. Journal of Trauma. 68: 415–420.

Hak DJ, Smith WR, Suzuki T. (2009) “Management of hemorrhage in life-threatening pelvic fracture”. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 17:447–457.

Geeraerts T, Chhor V, Cheisson G, et al. (2007) “Clinical review: initial management of blunt pelvic trauma patients with haemodynamic instability”. Critical Care. 11:204–213.

Durkin A, Sagi HC, Durham R, et al. (2006) “Contemporary management of pelvic fractures.” American Journal of Surgery. 2006;192:211–223.

Mohanty K, Musso D, Powell JN, et al. (2005) “Emergent management of pelvic ring injuries: an update”. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 48:49–56.

Friese G, LaMay G. (2005) “Emergency stabilization of unstable pelvic fractures”. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. 34:65, 67–71.

Biffl WL, Smith WR, Moore EE, et al. (2001) “Evolution of a multidisciplinary clinical pathway for the management of unstable patients with pelvic fractures”. Annals of Surgery. 233:843–50.

Hsu SD, Chen CJ, Chou YC, Wang SH, Chan DC. (2017) “Effect of Early Pelvic Binder Use in the Emergency Management of Suspected Pelvic Trauma: A Retrospective Cohort Study”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Oct 12;14(10)

Bottlang M, Simpson T, Sigg J, et al. (2002) “Noninvasive reduction of open-book pelvic fractures by circumferential compression”. Journal of Orthopedic Trauma. 16:367–373.

Prasarn ML, Small J, Conrad B, et al. (2013) “Does application position of the T-POD affect stability of pelvic fractures?” Journal of Orthopedic Trauma. 27:262–266.

Bottlang M, Krieg JC, Mohr M, et al. (2002) “Emergent management of pelvic ring fractures with use of circumferential compression”. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 84:43–47.

Routt Jr ML, Falicov A, Woodhouse E, Schildhauer TA. (2002) “Circumferential pelvic anti shock sheeting: a temporary resuscitation aid”. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 16:45–8.

Simpson T, Krieg JC, Heuer F, Bottlang M. (2002) “Stabilization of pelvic ring disruptions with a circumferential sheet”. Journal of Trauma. 52:158–61.

Bonner TJ, Eardley WG, Newell N, et al. (2011) “Accurate placement of a pelvic binder improves reduction of unstable fractures of the pelvic ring”. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 93:1524–8.

Shackelford S, Hammesfahr R, Morissette D, Montgomery HR, Kerr W, Broussard M, Bennett BL, Dorlac WC, Bree S, Butler FK. (2017) “The Use of Pelvic Binders in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 1602 7 November 2016”. Journal of Special Operational Medicine. 17(1):135-147.

Toth L, King KL, McGrath B, et al. (2012) “Efficacy and safety of emergency non-invasive pelvic ring stabilization”. Injury. 43:1330–1334.

Kreig JC, Mohr M, Ellis TJ, et al. (2005). “Emergent stabilization of pelvic ring injuries by controlled circumferential compression: a clinical trial”. Journal of Trauma. 59:659–664.

Knops SP, van Riel MPJM, Goossens RHM, et al. (2010) “Measurements of the exerted pressure by pelvic circumferential compression devices”. The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 4:101–106.

Knops SP, Van Lieshout EMM, Spanjersberg WR, et al. (2011) “Randomised clinical trial comparing pressure characteristics of pelvic circumferential compression devices in healthy volunteers”. Injury. 42:1020–1026.

Jowett AJL, Bowyer GW. (2007) “Pressure characteristics of pelvic binders”. Injury. 2007;38:118–121.

Prasarn ML, Horodyski M, Schneider PS, et al. (2016) “Comparison of skin pressure measurements with the use of circumferential compression devices on pelvic ring injuries”. Injury. 47:717–720.

Hedrick-Thompson JK. (1992) “A review of pressure reduction device studies”. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 10:3–5.

Knops SP, Van Lieshout EM, Spanjersberg WR, Patka P, Schipper IB. (2011) “Randomised clinical trial comparing pressure characteristics of pelvic circumferential compression devices in healthy volunteers”. Injury. 42:1020–6.

Vohra RK, McCollum CN. (1994) “Pressure sores”. British Medical Journal. 309:853–7.

Lerner A, Fodor L, Keren Y, Horesh Z, Soudry M. (2008) “External fixation for temporary stabilization and wound management of an open pelvic ring injury with extensive soft tissue damage: case report and review of the literature”. Journal of Trauma. 65:715–8.

Phillips TJ, Jeffcote B, Collopy D. (2008) “Bilateral Morel-Lavallee lesions after complex pelvic trauma: a case report”. Journal of Trauma. 65:708–11.