Advanced Airways - Supraglottic Airways

21st July 2014 revised 9th August 2021

Historically, Endotracheal Intubation (ETI) has been considered the ‘definitive airway’ but this advanced skill is not without its problems not least the difficulty, rapid skill-fade and serious consequences of a misplaced ET tube. As such, this technique, despite being regularly taught in some Medic Courses, should be reserved for experienced Healthcare Professionals.

Supraglottic Airways provide the advanced First Aider (with appropriate training) with additional options to protect the casualty’s airway whilst keeping within their skill-set. Developments in design have seen their efficacy and ease of placement mean that in some situations the advanced skill of Intubation is being replaced by a simpler, safer and, in some cases, more reliable method of airway management in both the pre-hospital and surgical setting.

A 2019 study (1) reviewing the US Department of Defence registry from 2007 to 2016 identified 194 combat casualties who received emergency cricothyrotomy and 22 casualties who received a supraglottic airway. They found no difference in short term outcomes for both groups inferring an underutilization of relatively simple supraglottic airways in favour of more complicated, high-risk, invasive procedures.

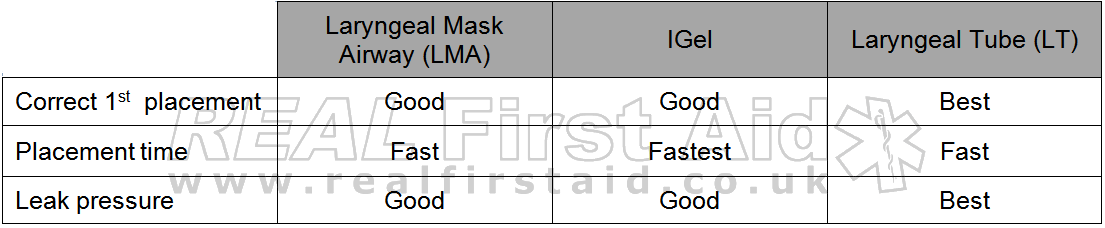

Comparison of Airway Adjuncts

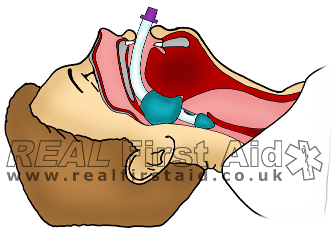

Supraglottic Airways extend down the airway to just behind the epiglottis; while their appearance varies, laryngeal airways work in a similar fashion – the ‘cuff’ creates a seal behind the epiglottis, which both holds the airway open while also preventing fluids from entering – either draining from above (e.g. blood or saliva) or stomach contents entering from the oesophagus.

Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA)

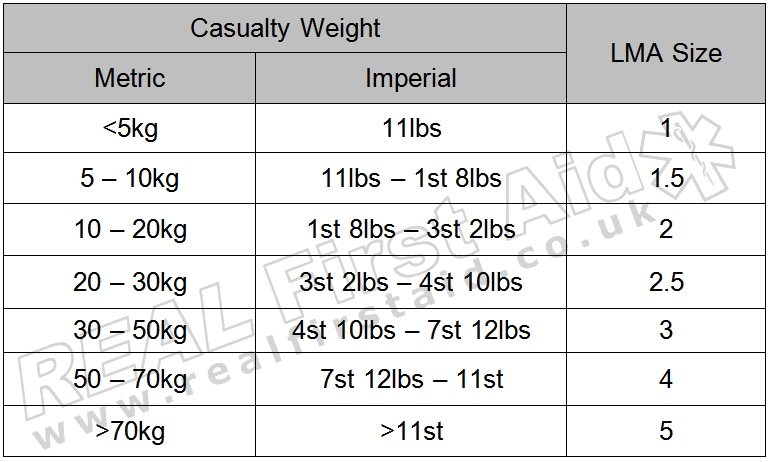

The LMA was the first of these devices to be commercially available as in the late 80’s. The inflatable cuff is inflated using a syringe and is available in the following sizes:

Whilst the size guide is fairly similar for all LMAs, the volume of air required to inflate the cuff is unique for each brand, therefore the volume should always be checked before inflation.

Size selection on a weight basis should be applicable to the majority of casualties; individual anatomical variations mean the weight guidance provided should always be considered in conjunction with an assessment of the patient’s anatomy. Patients with wide necks or wide thyroid/cricoid cartilages may require a larger airway than would normally be recommended on a weight basis. Obese casualties may require an LMA of a size commensurate with the ideal body weight for their height rather than their actual body weight.

I-Gel

Unlike the inflatable LMA, the cuff of the I-Gel is a soft elastomer that conforms to fit the laryngeal structure of the casualty, creating a seal. Because the cuff is not inflated like the LMA, this makes insertion significantly quicker (approx. 16s) than the LMA (approx. 26s) (2).

The effects of temperature:

It is a common misconception that because the I-Gel material is described as a thermoplastic, it expands to fit the casualty’s airway in the same way that an inflatable LMA would. The elastomer used in the I-Gel, SEBS (Styrene-Ethylene-Butylene-Styrene), is thermoplastic insofar as its softness and pliability is affected by heat, not its expansion. This misconception has lead people to believe that the I-Gel is not effective in hot environments because it has already ‘expended’ or that it may not be effective in a hypothermic casualty who does not have a core temperature high enough to warm the I-Gel enough for expansion.

These issues do not affect the I-Gel and is safe and effective to use across a wide range of temperatures (3, 4).

Correct placement

Whilst the I-Gel has the edge in terms of the speed of insertion, there is conflicting evidence that both the I-Gel and LMA are more likely to allow the user to correctly insert on the first attempt (5, 6).

There are challenges with the sizing: The sizing is based on a subjective estimate of the casualty, in Kg (where some are used to Stone or Pounds) and is based on the ideal body weight, not actual body weight.

A recent study (n-900) reveals that determining the appropriate size based on gender (Size 4 for females, size 5 for males) resulted in significantly fewer failures (n=13,3%) than using the weight-based formula (n=31, 7%). (7)

Leak Pressure

During positive pressure ventilation, air leaking around the cuff can increase the risk of “gastric insufflation”. The leak pressure of the I-Gel is comparable to an Endotracheal Intubation (8) and as good as (9), if not better than (3) the LMA.

Laryngeal Tube

The Laryngeal Tube (sold as the King LT in the US and VBM Laryngeal Tube in Europe) is a unique device featuring two inflatable bulbs; the distal bulb extends down into the oesophagus preventing aspiration of stomach contents and a larger proximal bulb which a) creates the seal which directs positive pressure ventilations down into the trachea and b) prevents fluids draining into the trachea from the nose or mouth.

Being inflatable, the Laryngeal Tube is not as quick to deploy as the I-Gel but the colour-coded syringe which is supplied is seen to make the LT significantly quicker to insert and inflate than the LMA (10, 11).

There is conflicting evidence over the Laryngeal Tube’s superiority over the Laryngeal Mask (12-14), but several studies have identified the Laryngeal Tube having high first-placement success rates of 89.7% - 90% (11, 15-18), and ease of use for both experienced professionals and lay rescuers. (19-21)

The LT airway does not have the inflation volumes printed on as the LMA does so if the dedicated syringe is missing you cannot inflate with another syringe, however, all sizes are inflated to a pressure of 60 cm H2O (or 44mmHg) and this can be done if you have a suitable cuff inflator of the style where the bulb and gauge are a combined unit.

Leak Pressure.

The Laryngeal Tube has a significantly higher leak pressure than the LMA. (17, 22-24).

Comparison of Supraglottic Airways

Correct Placement and Securing of Supraglottic Airways

Conclusions

Let's not be precious about equipment; the best equipment to use is the equipment you have with you so, as with all equipment, become familiar with it by regular practice.

All supraglottic airways provide greater protection than Oral or Nasal airways but there are slight differences:

For the Advanced First Aider and professional alike the I-Gel benefits from the sheer ease and speed of placement which is why it is, for many, the airway of choice even over Endotracheal Intubation. It can even be used to aid intubation in a difficult airway by acting as a guide once in place.

For the more proficient and practised, the Laryngeal Tube is more time consuming to insert but benefits from a more secure placement which is important for the casualty who is being ventilated (as opposed to the casualty who is breathing spontaneously) or the casualty who needs to be moved, especially over rough ground, on foot or in vehicles, where movement is at risk of dislodging the airway.

References:

Schauer SG, Naylor JF, Chow AL, Maddry JK, Cunningham CW, Blackburn MB, Nawn CD. April MD (2019) “Survival of Casualties Undergoing Prehospital Supraglottic Airway Placement Versus Cricothyrotomy“. Journal of Special Operational Medicine. 19(2). 91 - 94.

Helmy AM. Atef, HM. El-Taher, EM and Henidak, AM. (2010) “Comparative study between I-gel, a new supraglottic airway device, and classical laryngeal mask airway in anesthetized spontaneously ventilated patients”. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia. 4(3). pp131-136.

Chapman, D. (2012) “Is it really necessary to warm up first?” (online) http://daveairways.wordpress.com/2012/05/30/is-it-really-necessary-to-warm-up-first/ [accessed 16th July 2014]

Laprene© http://www.softergroup.com/en/products/Thermoplastic-Elastomers/Laprene?productid=37&prdName=Laprene¯ode=Thermoplastic-Elastomers [accessed 16th July 2014]

Kannaujia, A. Srivastava, U. Saraswat, N. Mishra, A. Kumar, A. and Saxena, S. (2009) “A Preliminary Study of I-Gel: A New Supraglottic Airway Device”. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. Vol 53(1). pp52-56

Ragazzi, R. Finessi, L. Farinelli, I. Alvisi, R. and Volta, CA. (2012) “LMA Supreme vs i-gel – a comparison of insertion success in novices”. Anaesthesia. 67:384–388

Guerrier G, Agostini C, Antona M, et al. (2019) "Choosing appropriate size of I-Gel® for initial success insertion: a prospective comparative study". Anaesthia Critcal Care and Pain Medicine. 38(4):353‐356.

Uppal, V. Fletcher, G. and Kinsella, J. (2008) “Comparison of the i-gel with the cuffed tracheal tube during pressure-controlled ventilation”. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 102(2):264-268

Van Zundert TC. and Brimacombe JR. (2012) “Similar oropharyngeal leak pressures during anaesthesia with i-gel, LMA-ProSeal and LMA-Supreme Laryngeal Masks”. Acta Anaesthesiologica Belgica. 63(1):35-41

Noor, Z.M. and Khairul, F. A. (2006) “Comparison of the VBM laryngeal tube and laryngeal mask airway for ventilation during manual in-line neck stabilisation”. Singapore Medical Journal. 47(10):892-6.

Wrobel, M. Grundmann, U. Wilhelm, W. Wagner, S. and Larsen, R. (2004). "Laryngeal tube versus laryngeal mask airway in anaesthetised non-paralysed patients. A comparison of handling and postoperative morbidity". Der Anaesthesist. 53(8):702–8.

Ocker, H. Wenzel, V. Schmucker, P. Steinfath, M. and Dörges, V. (2002) “A comparison of the laryngeal tube with the laryngeal mask airway during routine surgical procedures”. Anesthesia & Analgesia. Oct;95(4):1094-7

Cook, T.M., McCormick, B. and Asai, T. (2003) “Randomized comparison of laryngeal tube with classic laryngeal mask airway for anaesthesia with controlled ventilation”. British Journal of Anaesthesia. Sep;91(3):373-8.

Asai, T. Shingu K. (2005) The Laryngeal Tube”. British Journal of Anaesthesia. Dec; 95(6):729-36

Diggs. LA, Yusuf, JE. De Leo, G. (2014) “An update on out-of-hospital airway management practices in the United States”. Resuscitation. 85(7):885–892

Gaitini L et al. (2003) “An Evaluation of the Laryngeal Tube During General Anesthesia Using Mechanical Ventilation”. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 96:1750-5.

Asai, T. Murao, K. Shingu, K. (2000) “Efficacy of the laryngeal tube during intermittent positive-pressure ventilation”. Anaesthesia. Nov 55 (11):1099-102.

Asai, T. Shingu, K. and Cook T. (2003) “Use of the laryngeal tube in 100 patients”. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. Aug;47(7):828-32.

Russi, D. S. Miller, L. Hartley, M. J. (2008) “A Comparison of the King-LT to Endotracheal Intubation and Combitube in a Simulated Difficult Airway”. Prehospital Emergency Care. 12(1):35-41

Gahan, K, Studnek, J, and Vandeventer, S. (2011) “King LT-D use by urban basic life support first responders as the primary airway device for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest”. Resuscitation. 82(12):1525–1528.

Hagberg, C. Bogomolny, Y. Gilmore, C. Gibson. V, Kaitner, M. and Khurana, S. (2006) “An Evaluation of the Insertion and Function of a New Supraglottic Airway Device, the King LT, During Spontaneous Ventilation”. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 102:621–5.

Asai, T. Kawashima, A. Hidaka, I. and Kawachi, S. (2002) “The laryngeal tube compared with the laryngeal mask: insertion, gas leak pressure and gastric insufflation”. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 89(5):729-32.

Dörges, V. Ocker, H. Wenzel, V. and Schmucker, P. (2000) “The Laryngeal Tube: A New Simple Airway Device”. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 90:1220-2.

Cook TM, McCormick B, and Asai T. (2003) “Randomized comparison of laryngeal tube with classic laryngeal mask airway for anaesthesia with controlled ventilation”, British Journal of Anaesthesia. Sep;91(3):373-8.

Iserson, KV. (2012) Improvised medicine – Providing Care in extreme environments. London. McGraw Hill

Burns, SM. Carpenter, R. Blevins, C. Bragg, S. Marshall, M. Browne, L. Perkins, M. Bagby, R. Blackstone, K. and Truwit JD. (2006) “Detection of inadvertent airway intubation during gastric tube insertion: Capnography versus a colorimetric carbon dioxide detector”. American Journal of Critical Care. Mar;15(2):188-95.