In Defence of the SWAT Tourniquet

13th October 2021

Since the publication of “2019 Recommended Limb Tourniquets in Tactical Combat Casualty Care“ (1) the reputation of SWAT Tourniquet has taken a bit of a battering, but does that mean it should be relegated to the bin, along with the RATS and STAT (zip tie) tourniquet?

Whilst probably not as quick and easy to apply as some mechanical tourniquets, the SWAT still has it’s place.

The PACE acronym which is often used for Communication and Survival planning can also be applied to a layered approach to tourniquets based on risk assessment and appropriateness.

Primary - Our current preferred tourniquet is the Aero Healthcare RapidStop for a number of reasons including, but not limited to, its efficacy, mechanical advantage ease of use, greater modulation (per click versus each 180° windlass twist).

Alternative - Any conventional and recognised windlass based tourniquet, e.g. CAT, SOFT or SAM XT

Contingency - SWAT due to its small size, low cost and low weight and multi-functionality.

Emergency - Improvised. As long as the casualty has clothing and the responder has shears and something to twist, you will have an improvised tourniquet in an emergency.

TCCC Recommendations

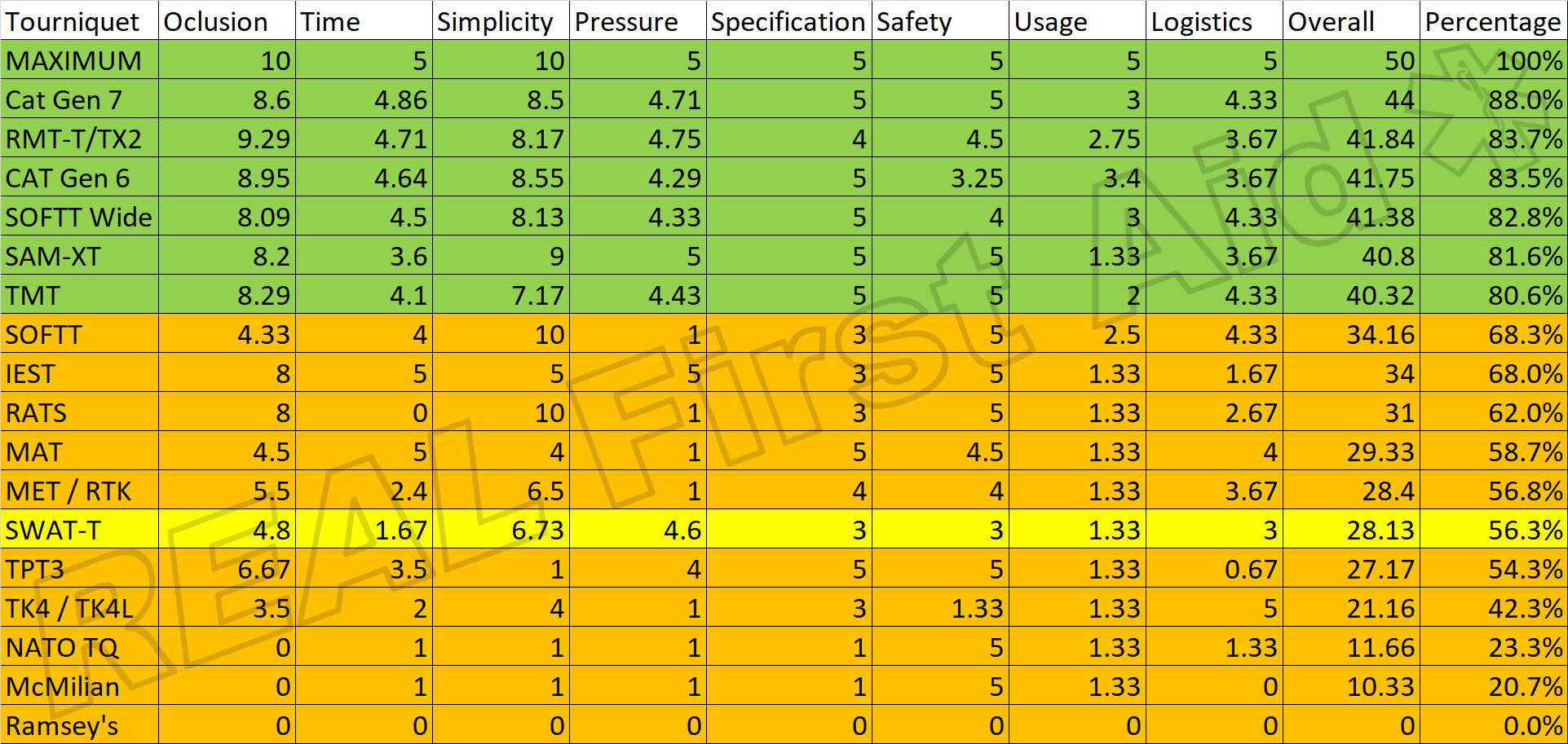

The publication from the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC) was interesting as it was a deep meta-analysis of a broad selection of commercially available tourniquets based on a number of criteria including time of application, ease of use, pressure applied and so on. Criteria were scored out of 10 or 5 to a maximum of 50 points. The cut-off was chosen as 40 points (or 80%) to warrant recommendation.

Those tourniquets that did not score at least 40 out of 50 were not recommended.

This, understandably, lead to the top-performing, such as the CAT, SOFT Wide and SAM XT tourniquets being externally validated in the wider medical community and, consequently, those which were not recommended were, understandably, dismissed or rejected.

Whilst we would not recommend the SWAT as a primary tourniquet, it has its place as a continency or Every Day Carry for a couple of reasons:

The TCCC Guidelines are specifically seeking recommendations for a Combat setting. This typically requires the casualty to self-apply their own tourniquet under the initial Care Under First stages of TCCC (2). This may also be the case where a tree surgeon may have to apply their own tourniquet but where a Responder is applying the tourniquet, the need for self-application is removed.

CoTCCC Recommendations do not mean they are universally recommended, or indeed, universally rejected in civilian settings.

Some of the assessment criteria were not of merit outside of a military setting, such as Logistics. The preference criteria were also skewed heavily to windlass designs given that all military and law enforcement personel have almost exclusive experience of windlass designs, typically CAT or SOFT.

There is questionable data used to score the SWAT Tourniquet.

Revision of the original data

Table 1 shows the original outcomes of the CoTCCC meta-analysis. It is clear to see that the SWAT tourniquet clearly falls way below the 80% threshold for recommendation.

Table 1. Original Data

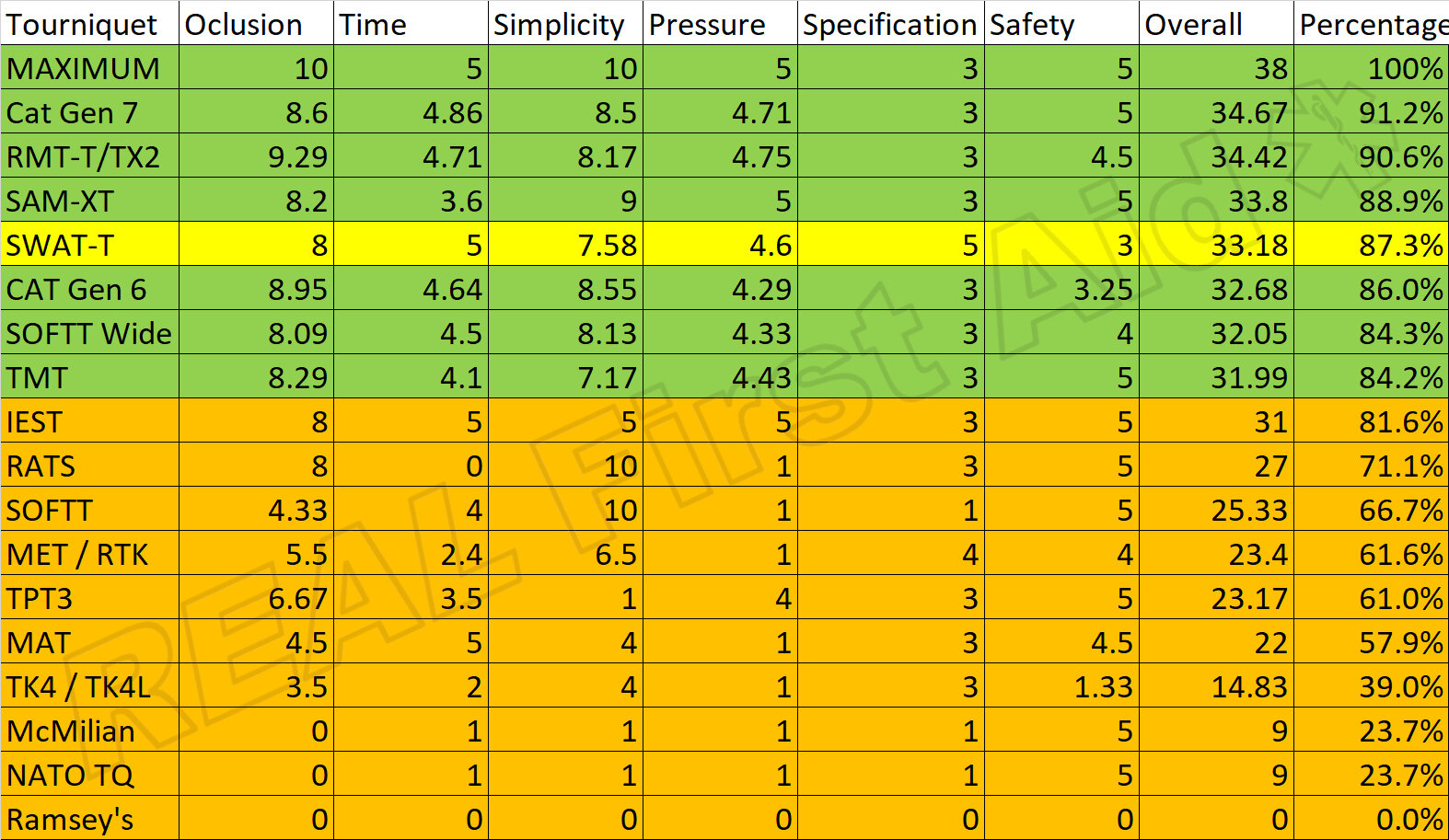

To revise the scores to a wider, non-military setting, the “Usage” and “Logistics” scores have been removed and the overall scores adjusted.

The “Usage” scores are heavily biased to those who have an almost exclusive experience of windlass designs which may explain why the CAT and SOFT design score so highly - being issued to US, UK and other western armed forces for nearly 20 years. The SAM XT is also a windlass design but scored poorly - possibly because whilst the mechanism is very similar, it is simply a different and unfamiliar design.

Logistics has been removed as this is solely relevant to military procurement and distribution.

Table 2. Removal of “Usage” and “Logistics” criteria.

With the removal of Logistics and Usage criteria from the table the SWAT score increase marginally but there are specific weaknesses: Occlusion Efficacy, Time to Application and Specification.

Specification

5 points are available here; a width of at least 1.5”, a length of at least 37.5”, a weight of less than 8oz, a locking mechanism and the ability to write the time on it.

A locking mechanism is required to ensure that any loose end that is snagged during transit or extrication of the casualty does not release the tourniquet. As the SWAT does not have a loose end when properly applied, there is no mechanical locking mechanism required - if one were to pull on any loose end, it would only tighten further.

The SWAT also loses points as it does not have a dedicated area to write the time of application….which is true if you use the tactical black SWAT but not if you use the preferred Orange SWAT. As such, these scores have been adjusted from 3 up to 5.

The same is true of the Israeli Emergency Silicone Tournwiquet (IEST) and the scores have similarly been adjusted to reduce bias.

Occlusion Pressure and Time to Application

The SWAT lost points in both of these criteria due to significantly lower than normal outcomes from two trials (3, 4) referenced as “27” and “31” in the article shown in Tables 3 and 4.

The poor outcomes from these two trials award the SWAT zero points for Occlusion Pressure and Time to Application, despite scoring well in all other research trials.

In another trial of 150 candidates, it scored moderately well and a further trial of 32 candidates awarded the design top marks for Occlusion Efficacy.

Speed of application was also deemed a Zero from the two trials, despite being awarded top marks from a third trial?

Why the discrepancy?

Possibly because the two trials in question were conducted by the US Navy, again, an inherent bias toward the CAT and SOFT designs which were, and still are, currently issued.

Table 3. Occlussion Efficacy orginal data

Table 4. Time to application

If these anomalies are removed from the scores, this changes the overall outcomes dramatically. Table 5 and 6.

Table 5. Occlusion Efficacy adjusted.

Table 6. Time to application adjusted.

Ease of Use

The same references “27” and “31” (3, 4) were used to contribute to the Ease of Use data and were similarly removed from the overall data.

Table 7. Ease of Use orginal data

Table 8. Ease of Use adjusted.

With the above revisions to the data, the SWAT now scores an impressive 87.3%, above the CAT Gen 6, SOFFT Wide and TMT. Table 9

Table 9. TCCC data adjusted.

Other Uses

An additional benefit of the SWAT tourniquet is that it can be used with haemostatic agents or plain gauze to hold wound packing in place in junctional areas, such as the neck, groin and axilla. This cannot be achieved as well (or indeed at all in some cases) with other tourniquet designs.

The SWAT can also be used to stabilise minor injuries such as ankles, wrist and knee (with caution given the high elastic nature of the material) as well as an improvised sling or for functional equipment repairs.

Conclusions

The TCCC Recommendations are a useful starting point for a broad comparison of a wide range of tourniquets available but:

The recommendations are geared towards a Tactical Combat setting

There is concern over the bias and objectivity of some of the data.

Not all of the criteria are relevant to a civilian or Responder setting.

Where one’s Needs Analysis suggests that Catastrophic Haemorrhage is reasonably predictable, two dedicated mechanical tourniquets should be carried at all times.

Where the likelihood of Catastrophic Haemorrhage is low, two SWAT tourniquets and two rolls of compressed gauze make a wholly appropriate cheap, light, small, contingency for both compressible and non-compressible bleeds in a medical bag or as part of an Every Day Carry, where it is not necessarily appropriate to always carry two mechanical tourniquets.

There is plenty of further evidence of the efficacy and appropriateness of the SWAT tourniquet as a Contingency tourniquet (5-9). Where poor outcomes have been identified in the literature, this is usually due to the unfamiliarity of the device and can be rectified with basic training. (10-12)

Very often, with all equipment, we favour what we are familiar with and what is fashionable. It is not so much about the kit you are using, more so understanding your kit, its application, limitations and time spent training with it that makes it effective or not.

References

Montgomery HR, Hammesfahr R, Fisher AD, Cain JS, Greydanus DJ, Butler FK Jr, Goolsby C, Eastman AL. (2019) “2019 Recommended Limb Tourniquets in Tactical Combat Casualty Care”. Journal of Special Operations Medicine. 19(4):27-50

Alvarez R, Cox DD, Dory R. (2015) “Joint Operational Evaluation ofField Tourniquets (JOEFT)—phase II. In: Naval Medical Research Unit–San Antonio. Fort Sam Houston, TX: Expeditionary and Trauma Medicine Department Combat Casualty Care and Operational Medicine Directorate.

McKeague AL, Cox D. (212) “Phase I—Joint Operational Evaluation of Field Tourniquets”. In: Naval Medical Research Unit–San Antonio. Fort Sam Houston, TX: Expeditionary and Trauma Medicine Department Combat Casualty Care and Operational Medicine Directorate.

Wall PL, Welander JD, Singh A, Sidwell RA, Buising CM. (2012) “Stretch and Wrap Style Tourniquet Effectiveness With Minimal Training”. Military Medicine. 177(11):1366–1373

Wall PL, Duevel DC, Hassan MB, Welander JD, Sahr SM, Buising CM. (2013) “Tourniquets and Occlusion: The Pressure of Design”. Military Medicine. 178(5):578–587

Ellis J, Morrow M, Belau A, Sztajnkrycer L, Wood J, Kummer T, Sztajnkrycer M. (2020) “The Efficacy of Novel Commercial Tourniquet Designs for Extremity Hemorrhage Control: Implications for Spontaneous Responder Every Day Carry”. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 35(3), 276-280 Medicine, 35(3), 276-280

Rometti MR, Wall PL, Buising CM, et al. (2016) “Significant Pressure Loss Occurs Under Tourniquets Within Minutes of Application”. Journal of Special Operations Medicine : a Peer Reviewed Journal for SOF Medical Professionals. Winter 2016;16(4):15-26

Wall PL, Welander JD, Sahr S, Buising CM. (2012) “Lighting did not affect self-application of a stretch and wrap style tourniquet”. Journal of Special Operations Medicine: a Peer Reviewed Journal for SOF Medical Professionals. 12(3):68-73

Portela RC, Taylor SE, Sherrill CS, Dowlen WS, March J, Kitch B, Brewer K. (2020) “Application of Different Commercial Tourniquets by Laypersons: Would Public-access Tourniquets Work Without Training?” Academic Emergency Medicine. 27: 276– 282.

Ross EM, Mapp JG, Redman TT, Brown DJ, Kharod CU, Wampler DA. (2018) “The Tourniquet Gap: A Pilot Study of the Intuitive Placement of Three Tourniquet Types by Laypersons”. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 54(3):307-314.

McCarty JC, Hashmi ZG, Herrera-Escobar JP, et al. (2019) “Effectiveness of the American College of Surgeons Bleeding Control Basic Training Among Laypeople Applying Different Tourniquet Types: A Randomized Clinical Trial”. Journal of the American Medical Association Surgery. 154(10):923–929